Noted scholar Laurent Gayer's recent title, Karachi: Ordered Disorder and the Struggle for the City, is an attempt to understand what drives violence in one of the world’s largest cities. He shares what makes it tick, the Mumbai-Karachi connect, and the Mohajirs with Kanika Sharma

Malala Yousafzai

Q. What motivated you to write the book?

A. I have always been fascinated with cities — the larger and noisier, the better. When I first visited Karachi in 2001, I knew that I had found my own ‘maximum city’. And while being interested in the local histories of its various settlements, I decided to adopt a synoptic perspective, which would try to make sense of the wonder that is Karachi, as a whole. Journalists and scholars alike denigrated it as a “chaotic city”, an ungovernable, utterly unpredictable urban mass. If I wanted to counter these dominant narratives, I had to adopt the same wide frame of analysis and show that, as a whole, Karachi does work despite and sometimes through violent unrest.

ADVERTISEMENT

A Pakistani youth places an oil lamp next to a photograph of child activist Malala Yousafzai as they pay tribute in Karachi in October 2012. Pic/AFP

Q. You describe Karachi’s violence as an “ordered disorder”. Is this unique to Karachi or is it because it was a former colony?

A. Karachi’s violent politics is in a permanent state of flux as the balance of power between public and private aspirants to authority and wealth is continuously shifting. I do not think that this violent configuration is specific to post-colonial contexts. Karachi shares many of its attributes with Colombian cities affected by the global economy of the drug trade, for instance. Thus, Karachi’s chronic violence is primarily an offshoot of the Afghan Jihad, which democratised the access to firearms and gave birth to lucrative criminal markets that dramatically upset the social and spatial fabric of the city.

Laurent Gayer, Scholar and writer

Q. You have also drawn several parallels between Karachi and Bombay/Mumbai. To what extent do you think the cities mirror each other?

A. These are two modern cities, which developed as colonial ports with a strong link to the oceanic trade – and in particular with the opium trade. In the Post-colonial period, these are two cities whose cosmopolitan ideals were dramatically challenged by muscular, plebeian ethno-nationalists who were determined to deny outsiders their own right to the city. The Shiv Sena and the MQM (Muttahida Qaumi Movement) share many similarities. However, the violence of the Shiv Sena remained physical, while the influx of modern weaponry in Karachi in the wake of the Afghan Jihad made the MQM’s violence much more technological and lethal.

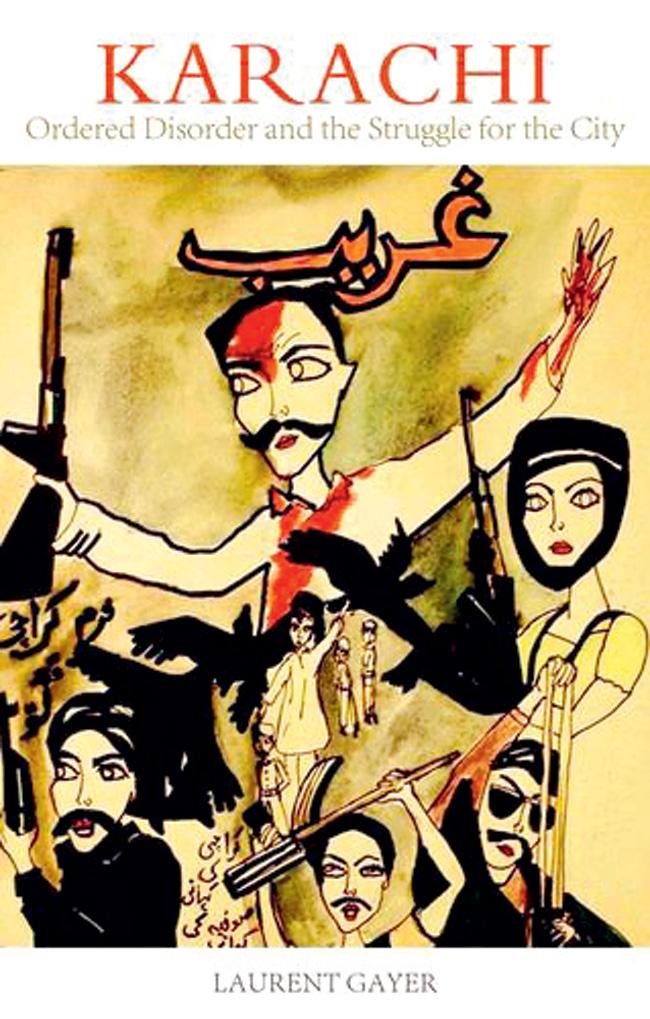

Karachi: Ordered Disorder and the Struggle for the City, Laurent Gayer, HarperCollins India, Rs 450. Available at leading bookstores.

Q. Is there a solution to the violence in Karachi, now that it is attributed with terrorism? How can the world and

India intervene?

A. Islamist terrorism is only one form of violence affecting Karachi. Everyday violence is mainly political and criminal. It is related to turf wars between political parties and criminal groups. However, in recent years, sectarian groups and jihadist organisations have also taken roots in the city and add up to this, the complex mix of ethnically, religiously and economically-tainted struggles for the control of the city and its resources. If India has a role to play here, it is in facilitating cross-border exchanges through a more liberal visa policy. Through family relations, the Mohajirs retain strong links with India. Facilitating these in the long run would contribute in defusing tensions between the two countries.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!