From Dadasaheb Phalke to Ritesh Batra, the National Museum of Indian Cinema will take the film buff on a behind-the-scenes look at the country's love affair

Bombay might have become Mumbai, while the rest of India has been in constant churn; yet, our connection with films remains intact. Celebrating the celluloid screen, talks of the Museum of Indian Cinema had been buzzing for a while. Now, that it is all up and shining, we entered into a wonderland that lets all age groups gaze at the images, give playback to golden jubilee stars like Rajinder Kumar and Dev Anand, and re-imagine the tableaux from the film, Raja Harishchandra by father of Indian cinema Dadasaheb Phalke, cast in marble prodding the audience to revisit the 20th century.

ADVERTISEMENT

A complete film set is recreated with lights, camera and sound equipment in order to give a feel of the shooting.

Cine call

“The idea is to discover and be filled with wonder irrespective of age when you walk into the museum,” informs film historian Amrit Gangar who has been arduously putting memorabilia, old cameras, artefacts for the past one year, in tandem with the National Council of Science Museum, Kolkata. Gulshan Mahal, the 19th century bungalow — an evacuee property of Peerbhoy Khalakdina who belonged to the Khoja family from Kutch — covers 6,000-sq feet within the Films Division grounds. After serving as a hospital to Jai Hind College, the nine-room bungalow has been restored to its original grandeur by the National Building Construction Corporation.

The Lumiere brothers projected the first private screening of a film in 1895, an iconic moment in cinema. Pics/Bipin Kokate

“Sensuousness is a major part of the museum as it is of cinema”, Gangar informs. One can touch all kids of equipment, blow up posters of films on a gigantic touch screen, shoot their own films, and lastly, sing and listen to old favourites. Anil Kumar, distribution coordinator, explains, “Cinema is all about moving images, thus, a multimedia set-up was a necessity.”

Screen saviours

As soon as one enters the cream coloured villa, echoing sounds, illuminated statues and several artefacts flood the senses with choice to hear, listen and play. The central hall initiates the visitor into the concept of cinema, nudging him to embark on a journey that will easily take “five to six hours,” says Gangar.

Not only that but plans to show silent cinema with live music and sessions by eminent directors who will relate their shooting process, are on the cards as well. The Jehangir Bhownagary Bhavan located at the left of the museum will be the decided venue, for its 200-seating capacity and multipurpose function. The inauguration of both venues will take place simultaneously as soon as the Ministry of Culture gives it a nod.

At: 24, GD Marg, Cumbala Hill, Films Division, Pedder Road.

Call: 23864633

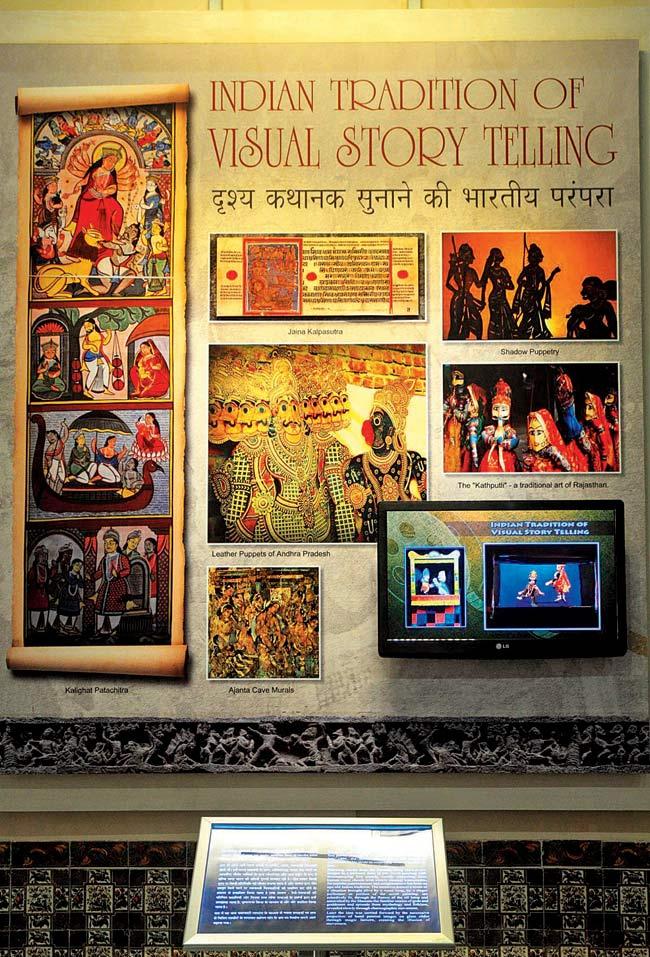

We, the storytellers

The museum is clearly defined by a strong emphasis on Indian character in the history of cinema. The initiating point in the museum then are the various traditions of storytelling in India. From chitrapat to Jain kalpasutras, the point is driven home, so that viewer takes pride in understanding how early the idea of cinema had become rooted in Indian imagination. For instance, Gangar shares, “Chitrapat work comes from pat chitra parampara” that can be described as a series of images wound up on a scroll. The art form precedes the European movie-making techniques and is definitely before 19th century. “The centuries’-old tradition of Orissa can be described as a motion picture in a generic way,” surmises the historian, adding, “There was a desire in the human mind to create a moving picture on the screen. Just like the Altamira Caves where the Homo sapiens drew the running bison.”

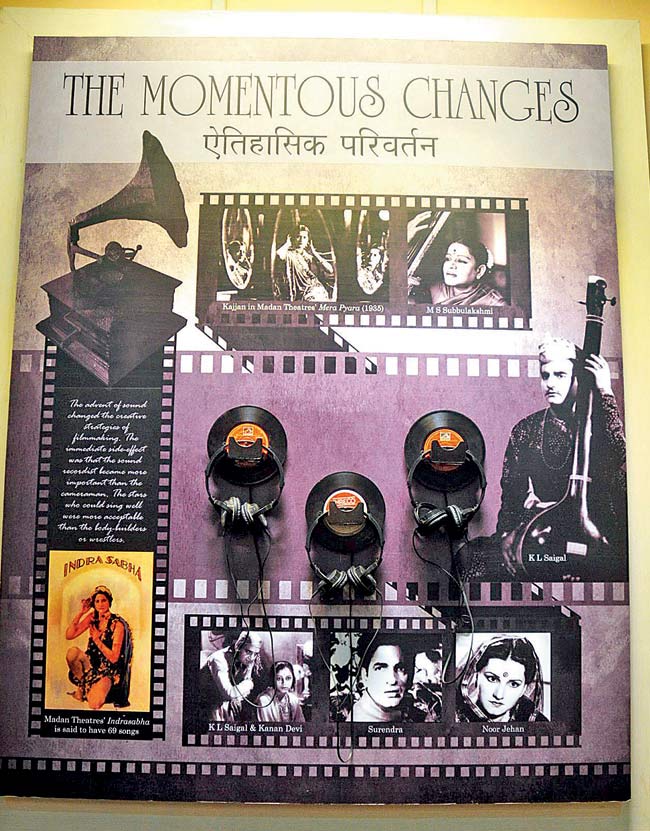

Playback pride

“The credit for producing the first sound film in India goes to Imperial Film Company that produced Alam Ara in 1931,” recounts Gangar. Songs for a long time were sung by the actors involved in the early stages of cinema, “which were recorded on the spot, but then a revolutionary concept of the playback was invented and the actors were not required to be singers,” he informs. Dhoop Chhaon (Hindi) and Bhagya Chakra (Bengali) were the first films to have playback and were purely an Indian invention as per some sources. “The film was directed by Nitin Bose and its sound recordist was his brother Mukul Bose; its music was composed by Rai Chand Boral. Arguably, Nitin Bose and Mukul Bose invented the playback system in India while shooting for this film. As Nitin Bose claimed later, it was one of the first films in the world to have used the playback system,” asserts the scholar.

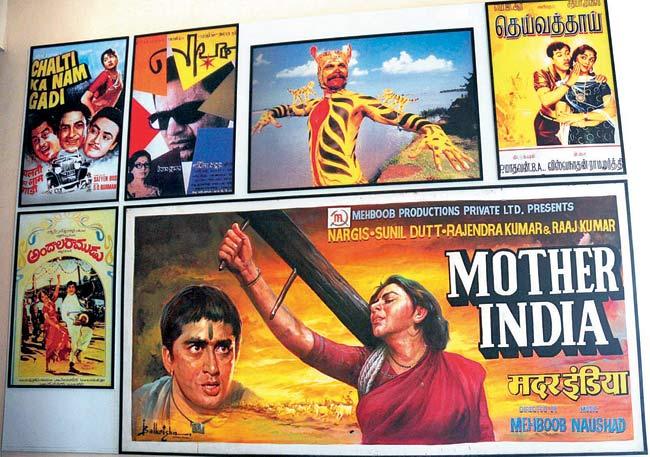

Get hold of film memorabilia

The museum is a treasure trove of posters, song booklets, lobby cards and hand bills. This kind of literature acted as second- hand information for the audience, we are told. One can see an original Mother India poster painted by Baburao Painter in the museum, “who was believed to have designed the first of the Indian film posters”, in Gangar’s words, adding, “As the talkie era began, the song booklets were for film publicity.” Glancing through the Mother India booklet, we saw all the lyrics written in Hindi and Urdu plus vital information on the film.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!