A students’ production traces the origins of Kathak, paying tribute to its multi-hued rich repertoire

Filmmaker Satyajit Ray's Shatranj Ke Khilari portrayed an indulgent Mughal emperor, Wajid Ali Shah dancing with ladies of the court.

Filmmaker Satyajit Ray's Shatranj Ke Khilari portrayed an indulgent Mughal emperor, Wajid Ali Shah dancing with ladies of the court.

ADVERTISEMENT

The nawab wrote thumris and choreographed splendid Kathak dances to sensuous lyrics, unmindful of British soldiers planning to annex his kingdom of Awadh.

This picture of an unruffled art patron has stayed with Mumbai-based Kathak performer-choreographer-teacher Sanjukta Wagh.

Its impact is so deep that it finds its way in some form in her work, just as it did in her latest collabourative student project 'Katha-Nazaakat-Renaissance-Now.'

Wajid Ali Shah dressed up as Krishna playing raasleela with the gopis of the court is an interesting reference etched in this "performed history" of Kathak. It speaks of an ingenuous effort to understand the Kathak dynamic.

Dancers get guidance from their teacher Sanjukta Wagh as they master their moves

"The history and politics of arts just converge effortlessly in the key images of the film. I plan to revisit the film with my students, as we are currently tweaking the students' project for a larger audience," says Wagh, who feels strongly in favour of an exploration of the concentric space between the old and the new in any art form.

History and the Body

'Katha-Nazaakat-Renaissance-Now' emerged from an assignment in which Wagh asked her students to study Kathak history and place themselves in it. The assignment involved the teacher as much as the students, because Wagh, after years of learning the Kathak pedagogy, felt an inner compulsion to "embody the history of one's form."

Practice makes perfect is a mantra that works when it comes to dance

Practice makes perfect is a mantra that works when it comes to dance

She felt that understanding the history of the form brings the practitioner closer to what she or he renders. "When you unfold all the diverse energies that have gone into the making of the form, it humbles you. You begin to look at yourself as a carrier of tradition. You know of the 100 possibilities of the form," Wagh states.

A tapestry of tradition

The brief was clear: chart the non-linear history of Kathak, accounting for every influence the 3rd century BC kathakars (storytellers), the Bhakti movement, the transition to the Mughal courts and formation of the three Kathak gharanas/schools of influence, and finally today's Indian artistes in whose bodies the form dwells now.

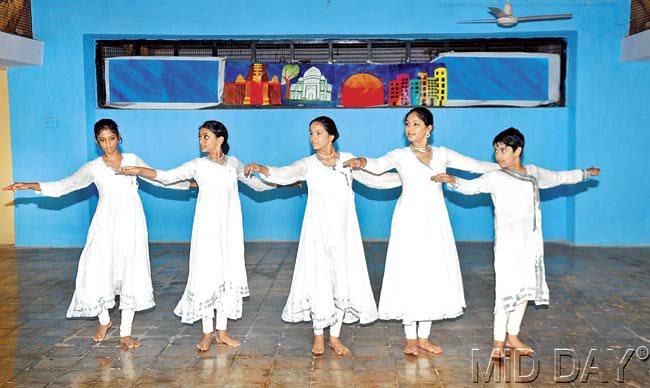

Kathak dancers practice their moves at TIFR dance class in Colaba. Pics/Bipin Kokate

"The idea was not to merely follow the chronological periods, block by block, as is done in a text book. We wanted all the influences to be interwoven in an idiom that matches the beauty of Kathak."

TIFR Base Camp

Wagh's eight students of varying school and college-going ages (11 to 18) stayed in the same precinct of Mumbai, the residential quarters of the Tata Institute for Fundamental Research (TIFR) in Colaba. While their fathers (some mothers too) carried out basic research in physics, mathematics and science education, these eight reveled in Kathak.

They pursued diverse academic disciplines in the morning, and then gathered for a different joy in the evening. Ipsita Srinivas, Asmita Gattamraju, Vaishnavi Panyam, Samhita Radhakrishna and Abhay Tole Trivedi were among the schoolgoers, whereas relatively older Samyuktha Rajan and Aashraya Gattamraju were pursuing science and arts respectively in South Mumbai colleges. The seniormost student Ira Chadha-Sridhar pursued law. Interestingly, Abhay's mother, Dr Shubha Tole, (46) professor of neurobiology at TIFR also played a small part.

History project

Wagh's Kathak dance class in TIFR took root 11 years ago. Today, she has around 27 Kathak students, of which eight are part of this history project. Many of these are learning the ropes since they were four years old.

As one of the younger students (and the only male in the student project) Abhay Tole (12) says, "Kathak bound us together under a basement roof every Tuesday evening and Sunday morning. We had experienced a dance form for quite some time.

We had argued and asked questions. We had practiced for hours. But the assignment challenged us to put together what we had soaked. The exciting part was that this time 'We' were the bodies that would bring the history alive."

Eye on Anatomy

Unlike a traditional dance class, each day would begin with a warm up. Wagh would ask them to concentrate on body parts and their interconnectedness. For instance, the elbow and its range movement in a Kathak presentation. She asked them to relate to the form in their preferred mode, what she terms as "letting them be."

For some students, the individual artist's exploration of the space was key, a few (like Aashraya Gattamraju) concentrated on the evolution of the thumri in the Mughal era; whereas some looked at the pure maths in the structure of a conventional tukra (short composition) or toda (long one) which follows a time cycle broken into triplets or quintuplets!

At regular intervals, Wagh would inspect their inputs and encourage them to experience the present-day manifestations of Kathak at Mumbai's NCPA auditorium or whichever space they could visit in this city of distances. The field visits were interspersed with workshops and orientation lectures, so that the Kathak genealogy was mapped well in their minds.

The four words

A workshop on the history of Kathak by sociologist Gita Chaddha unravelled hidden connections, whereas another conducted by Avantika Bahl Goyal added a whiff of contemporary dance and contact improvisation. Actress Yuki Ellias sensitised them to mime.

Choreographer Mandakini Trivedi spoke on the Nataraj motif and its cultural significance. Amid the process of reading and compiling information, students were asked to think of words which encapsulated each period of influence.

They came up with multiple options and finally chose four: 'Katha' for the storytellers' phase, 'Nazaakat' for the Mughal era, 'Renaissance' for the colonial and post-British period, and 'Now' symbolizing the contemporary Kathak artistes, ranging from Pandit Birju Maharaj to Rajashree Shirke.

A river flows

In the course of comprehending the distinctive features that characterize Kathak, students arrived at the metaphor of a watercourse to signify Kathak's fluid form. The script portrayed a meandering stream which is joined by tributaries.

The river collects sediments, energies, artistes, compositions, forms (found and lost), resonances and present-day spins and versions. Set to instrumental music, rhythm and footwork, the script (in English but interspersed with Hindi lyrics) personified Kathak through the ages.

One of the presenters, Samyuktha Rajan feels, "When I started learning Kathak at the age of five, I never thought of its form and texture, certainly not the preceding generations which brought glory to the form. I did it because my parents introduced me to it. Today, when I am a part of the "Katha-Nazaakat-Renaissance-Now" team, I recognise the treasure I hold in my hands."

Whirling on further

"I think history of an art form or otherwise, is often taught in a boring, linear and pit pat way in most schools. It can be made more multi-layered," says Wagh. For instance, the script explores the genesis of the signature spins (chakkars) of Kathak dancers in the Renaissance period.

It is found that symmetry became a yardstick in this era. The chakkar goes very close to the whirling dervishes of Turkey, the twirls of the Rajasthani folk dance and the one legged pirouettes of the Ballet. Students of history will enjoy the unfolding of such a legacy. An art form could be a window to other aspects of study like art patronage, aesthetics, social mores, political initiative and philanthropy.

Expand, not contract

The best part of the Kathak exercise is its attitude. While devoted to the art form of Kathak, it embraces a larger world view, credit for which surely goes to Sanjukta Wagh's multi-disciplinary approach to the arts. She encourages her students to take to multiple passions, from law to karate to salsa to Satyajit Ray.

Her own work reflects an eclectic range. She has been trained under the late theatre director Chetan Datar. She has received training of Hindustani music under Pandit Murli Manohar Shukla. She pursued post graduation in dance at London's Laban school.

For three years, she has been the dance curator at Mumbai's Kala Ghoda Arts' Festival. Her assignments of the recent past are strikingly unlike each other, building new pools of talent. Wagh has been leading the Beej interdisciplinary initiative to explore the contemporary world of expression.

As the 34-year-old artiste says, "In a world where pat answers and five minute television spectacles of talent are being hyped as dance, Beej's individualised approach to training gives importance to collective energy and basic rigour. For empowerment of the young artiste, it is imperative that discipline and abandon walk hand in hand."

For the uninitiated

Kathak's "performed history" is as much for the insider as it is for those who don't know much about it. It seeks a climate of appreciation and responsiveness. "Once I told someone, that I learn Kathak and he said, 'Oh, that thing where you paint your face green, isn't it?'

If he had some idea of what Indian classical art forms stood for, he could have risen above that level of response," adds one of the students who feels that classical forms are 'generalised' too casually by the general public. Madhavi Kumar, a parent who saw the first student show at TIFR, says she always held Kathak as a secular form which had accepted Muslim, Hindu and British influences.

"Many years ago, I chose Kathak for my daughters because I thought it was an open and porous form. My opinion was not based on any study, but some general knowledge and a gut feeling. When I saw the 'performed history,' I was happy to see my theme come alive." Wish Kathak brings similar joy to many more parents!

The writer is a Mumbai-based cultural chronicler

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!